A Minimum Viable Product (MVP) is generally understood as an early, basic version of a product that could be released to the public or shown to users to gather feedback. Starting with the minimum requirements allows teams to focus and iterate on a smaller set of features before adapting to feedback, making improvements, and adding other features.

In less ideal situations, an MVP is used as a target to aim for before the project’s deadline is up or the budget runs out. In these scenarios, teams build up to the MVP version of the product, and if there’s still time and money anything extra they can get done is icing on the cake.

Are these interpretations of MVP the best we can do? Is an MVP just a tangible deliverable for a project? Or can we treat MVP as a mindset that we can adopt in other areas to build better products?

MVP as Progressive Enhancement

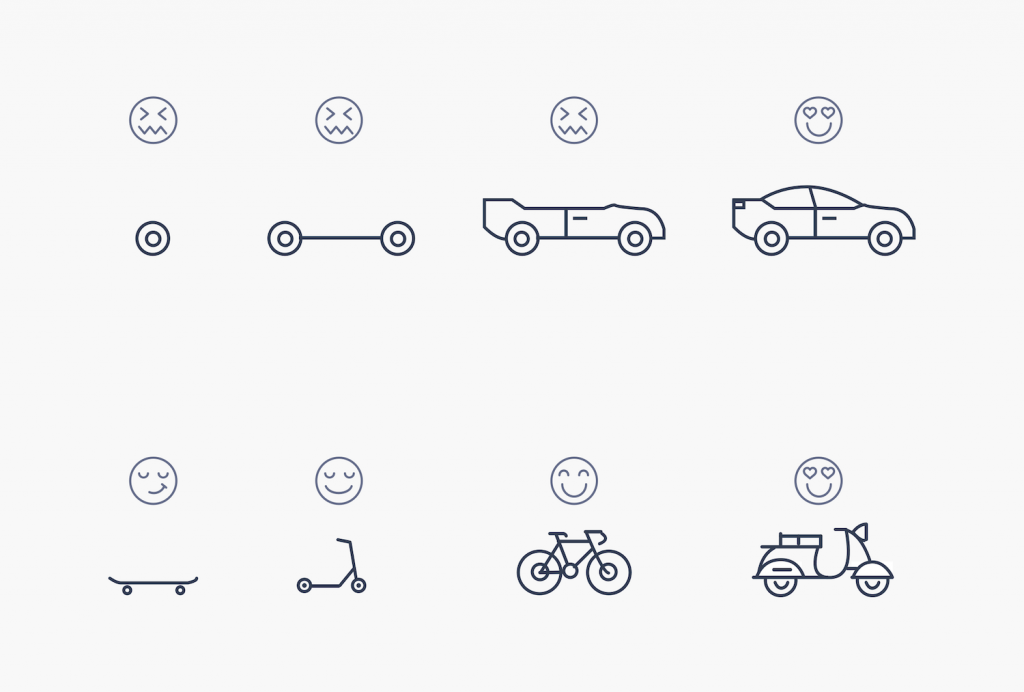

The concept of an MVP doesn’t have to apply to a whole product, it can apply to components or features as well. And, as it turns out, it applies well to the principles of progressive enhancement.

For those unfamiliar with the concept, a website built with progressive enhancement in mind is one that starts with baseline, essential functionality and then adds in extra functionality to enhance the experience for users. When applying progressive enhancement to the web, HTML is the baseline, CSS helps with layout and aesthetics, and JavaScript enables more interactivity.

For any frontend component, you can think of HTML as the MVP—adding CSS and JavaScript as needed enhances the component. Instead of MVP, we can think of this as a Minimum Viable Experience (MVE).

Progressively Enhanced Accordion

For example, say you want to build a Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ) section on your website and you’d like to make it so that clicking on a question shows or hides the answer. In development circles, we call this an accordion.

What’s the minimum viable version of this? It’s not essential for the click-to-expand behavior to exist, so to get started you could build the FAQ as a group of headings and sections that are always visible. Looks good to me, ship it!

At this point, you could decide to work on something else that’s more important or you could decide to work on supporting the expand/collapse accordion behavior. Since you already have a strong foundation in place you should be able to make minor enhancements to provide that additional functionality. As a next step, you could use the details element and put each question in a summary tag.

<details>

<summary>

How can I build a simple accordion component?</summary>

You can use the native details/summary tags provided by HTML5. Browser support is really good, and the fallback in unsupported browsers is still accessible.

</details>

Then if you need more advanced functionality, such as making it so only one answer is visible at a time, you can augment the Accordion with JavaScript. At every stage in this process, you have something that works, even if it doesn’t 100% match the original design.

Progressively Enhanced Mobile Navigation

Hamburger menus are ubiquitous for websites on small screens, but they’re something of a hassle to implement and can be prone to accessibility issues. By thinking in terms of MVP, you might be able to find a simpler solution that still meets the basic requirements. So what would happen if you just… didn’t make a hamburger menu? Maybe to start you could let the links in the header wrap to a new line, or you could show a link on small screens that jumps to a site map in the footer.

Once that baseline functionality is supported, you can move on to something else if it’s acceptable or you can layer in the extra complexity needed to make the hamburger menu work well.

Thinking in terms of MVP creates a subtle reframing of the underlying requirement. Instead of, “as a user, I need to be able to open a hamburger menu to find navigation links,” the requirement becomes, “as a user, I need to be able to find my way around the site.” By thinking about the core needs of our users, we can think outside the box and come up with simpler solutions to these sorts of problems.

MVP Build Processes and Tools

MVP thinking doesn’t only apply to the output of our work (the thing we’re building). It can also apply to the tools that we choose to build with. Before starting a project, ask yourself what tools are actually necessary to build the thing you’re working on.

All You Need for a Website is an HTML File

The amount of tooling typically used in web development is a common complaint, especially among developers who are early in their careers or just starting to learn web development. It’s not at all unusual to join a project that’s already underway and have at least 5 different configuration files for various tools used by the project, which is a lot to ask of someone new to wrap their head around. These tools are definitely useful, and there’s a reason developers reach for them, but are they all necessary? More specifically, are they necessary for your project?

The tools we use all the time are usually optional. If you have a super simple static website, all you really need is a single HTML file. That’s about as MVP as it gets. You can put your CSS in a style tag and any JavaScript in a script tag then chuck that onto a static file server and bingo! You’ve got yourself a website. Is this a viable option for every project? No, but this is a friendly reminder that there’s a spectrum between index.html and create-react-app.

The Dreaded Third-Party Dependency

Do you need a CMS yet? Or cloud hosting for images? Do you need that third-party library or build tool yet? If your project is in the early stages and the answers to those questions aren’t clear, maybe hold back and build things a little more manually. Then once you start feeling the pain of not having those tools, then you can reach for them.

The “You Ain’t Gonna Need It” (YAGNI) principle is all about avoiding unnecessary or over-engineered solutions to problems. By keeping MVP in mind, you can narrow your focus to what you actually need. And only when the need for a tool becomes clear should you add it to your toolbox.

Case Study: CMS Migration

Migrating content from one Content Management System (CMS) to another is not something one would typically associate with MVP. It’s either migrated or it isn’t, right? What’s the MVP version of that? Let’s take a look at a recent project where we were able to speed up a large migration effort by thinking in terms of MVP.

A client we worked with recently was using a CMS that was approaching the end-of-life support window. They had a new CMS in place and our job was to help them migrate the content from the old system to the new one.

However, they had thousands of pages to move and a rapidly approaching deadline.

The Typical Process

For most of the project, the process for migrating pages looked a little something like this:

Audit pages from the old system

Categorize pages based on the old CMS classification system

Identify components that needed to be built for the new system

Design content models for the new components and set them up in the new CMS

Build components for the new system that matched the content models

Write migration scripts that turn data from the old CMS into entries in the new one

Test the migration scripts against a test environment

Run the migration scripts against the main environment

Go through QA testing before making the pages go live

So that’s a lot. Unfortunately, there’s not really an MVP version of this workflow–omitting steps would have led to bugs and missed requirements. This process was understandably very time-consuming, even for the categories of pages with reliable data and predictable formats.

Then there were the other pages. The grab-bag. The one-off weird pages that didn’t match anything else on the site. We had about 800 pages like this that would have been impossible to migrate with the existing process within our timeline. We needed to improvise.

The MVP Process

Let’s put our MVP hats on, take a step back, and look at the requirements. The old CMS had to go. The new CMS was set up, and its data was being consumed by a Next.js application. The remaining pages were the lowest priority pages because of low traffic or low risk to the business. There were little to no back-end requirements for these pages–they were mostly static content. What if we just copy-pasted them, so to speak?

There’s a little more nuance to this of course, but in principle, if we could grab the output from the old CMS (the HTML served up to browsers), then we could use that to construct static files that we could serve from a public folder in our Next.js application.

The new process looked like this:

Write a script that:

a. Fetches and parses the HTML for a given page

b. Fetches any external resources used by the page

c. Writes those external resources to disc

d. Updates URLs in HTML to point to the new locations of those resources

e. Writes the HTML files to disc

Run the script against the pages we needed to migrate

Copy the resulting files to the public folder of our Next.js application

Adjust our redirects and configuration to serve those files correctly

This may look about as complicated as the typical process, but we’d only have to do these steps once, rather than once for every unique type of page that had different data, components, and edge cases to account for. As far as MVP goes, this is a pretty great reduction in the amount of work needed to achieve the same(ish) results.

The Result

By no means was this an easy alternative, but it was one that we could do within the timeline with relatively low risk and acceptable tradeoffs. The pages that were migrated this way would be harder to maintain since a developer would need to manually update the HTML files instead of just updating content in the CMS. However, by increasing the speed of the migration, we were able to meet the core needs of our client: getting 800 (or so) pages off the old CMS so it could safely be shut down. This also gave us time to focus on higher-priority pages that needed to be migrated more deliberately.

Even though this isn’t a situation you would normally think of as MVP, it absolutely is an MVP solution. We were able to find a strategic alternative to doing a huge amount of work, and now the client will be able to prioritize recreating those pages in their CMS as the business needs dictate.

MVP Is More than a Deliverable, It’s a Mindset

Rather than viewing MVP as a half-baked version 1.0 of a product or a drastically reduced estimate so you can get funding for your project, let’s shift our way of thinking. We can use the MVP mindset in our daily work by always looking out for ways to simplify features, reduce complexity, and refine our requirements.

As with accessibility, performance, and security, MVP thinking should be part of every step in the development process. Designers can work with developers to come up with design options that are easy to implement. Developers can focus on core requirements before layering on complexity. Project managers and product owners can help prioritize work and clarify what is truly essential for a project. Thinking in terms of MVP is essential for strategically minimizing effort while still delivering something useful. Working in this way, especially when coupled with progressive enhancement, is a great way to build resilient products. Keeping things basic also allows teams to be more nimble in implementing and iterating on business needs which is ideal for showing value to users and stakeholders quickly and being able to enhance features as needed.

So let’s stop thinking about an MVP being a deliverable that happens once at the beginning of a project, then is never mentioned again. Let’s expand our definition to treat it more like a guiding principle that we can use to build better products and improve our workflows.